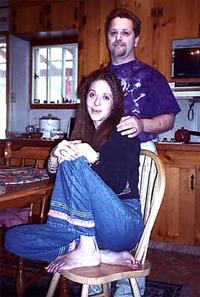

Jane Parker of Annapolis County has permission

from the federal government to smoke marijuana

to ease the pain caused by multiple sclerosis.

Husband Gary Kilburn says the relief begins

within minutes.

Pot's the only thing that eases woman's pain

By Peter Duffy

The Halifax Herald Limited

Monday, October 7, 2002

THE MARIJUANA issue hasn't been mentioned yet by either of us. Sipping tea in Jane Parker's living room, I wait for her to raise the topic. Which is silly, really. After all, it's the drug thing that's brought me here to this straggle of houses on the South Mountain, near Bridgetown.

Jane Parker is a rare individual; she smokes marijuana on a regular basis, and it's all quite legal. This mother to seven has Ottawa's permission to smoke it for medicinal purposes. Jane, 40, was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis four years ago. She says only marijuana offers her a modicum of relief from the pain. "This was not my first choice of drug," she assures me. "I tried everything they gave me (but) I got tired of living with the side effects." Jane is one of 834 people who has Health Canada's permission to possess marijuana for health reasons. Of that number, 700 may also grow their own. Jane is one of them, too.

This feisty woman contacted me, shocked and angered by criticism I'd levelled at another sanctioned marijuana smoker. "Coming from you," she'd remarked, "I wondered how the rest of world felt about us." So here I am, hoping to learn what life is like for someone in such pain that she resorts to an illicit drug for relief. Frankly, this isn't easy for me. I don't do drugs and have little time for those who do, especially the hard kind. Not that I'm perfect. I tried marijuana back in the 60s, but it didn't do anything for me. Jane, too, tried marijuana when she was younger. Like me, she wasn't a big fan. "I gave it up for motherhood and alcohol," she remarks, grinning.

But then came the multiple sclerosis, the same disease which was to claim her mother last December at age 61. Jane was in such discomfort that she took up marijuana again in 1998. She can't work and has no private medical insurance. Her only income is a federal disability pension of $7,000 a year. Despite her battle, she hasn't given up on life. She's studying for a nutritional practitioner's degree, which will allow her to teach others how to eat properly and use vitamins in their diet. Gary Kilburn, whom she married a year ago, is with a private security firm.

As we chat, Jane arches her back, trying to get comfortable on the sprawling old couch. "I took it for granted for 36 years," she says through gritted teeth. "The feel of grass beneath my feet, the feel of my hair through my fingers." "And now?" I ask She shrugs. "Every time I walk, it feels like sharp shards of red-hot glass going through my feet and up my back." She says even her toes are affected. I lean forward. Sure enough, they're twitching uncontrollably.

Jane neither sleeps nor eats properly. She's as slender as a whippet, standing 5-7 and weighing barely 110 pounds. These days, she rarely leaves the house because of the pain. "It's unrelenting," she says. And because she falls down a lot, she's equipped with a cane, a walker and a wheelchair. She's also incontinent. She rolls her hazel eyes. "This disease doesn't have the decency to kill you outright," she growls. Life is "stolen from you day by day." Gary kisses her forehead. "I feel helpless," he says. "There's not a lot I can do except try to look after her." Jane has given up on prescribed medications because of the side effects. Today, the only one she takes is clonazepam, a sedative. And, of course, the marijuana.

As we talk, she rises unsteadily from the couch, takes a regular cigarette from a pack, lights it and shuffles to the open back door. There, she squats, blowing the smoke outside. "I didn't want my second-hand smoke blowing in your face," she calls to me. Concerned about her frail health in the chill morning draft, I beg her to return. "You'd rather be smoking a joint, right?" I exclaim as she sits. She nods, the pain in her eyes now quite noticeable. I urge her to do what she has to. Eagerly, Jane stubs out the cigarette, goes into the kitchen and returns with a lit joint. She says it's her third this morning.

Easing onto the couch, she closes her eyes and inhales deeply. The pungent aroma fills the room. Within minutes, literally, Jane is a changed woman. The arched back is gone; her limbs are relaxed; even her toes are still. The effect is remarkable. So is her determination to continue using marijuana, even if she has to do it illegally, just like before - which, she tells me, may soon be the case. Saturday, Part 2: Ottawa changes the rules, causing a crisis for Jane.

>> Part 2 <<

New rules, however, are threatening her situation.

Red tape slows getting pot for pain

Saturday, November 16, 2002

By Peter Duffy

The Halifax Herald Limited

SHE PUTS what's left of the joint in the ashtray, sinks back into the couch and closes her eyes. Moments ago, she was in such pain that her back was arched and her limbs were stiff. Now, she's snuggled into the cushions, wiry frame relaxed, bare feet no longer twitching.

Even to someone as opposed to drugs as I am, it's hard not to be awed by the difference in this 40-year-old. "It still hurts," she murmurs, "but it's not as bad as it could be." Jane was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis four years ago.

Her husband, Gary Kilburn, stands behind her, stroking her long dark hair. "In all the years I've lived with Jane," he remarks, "I haven't seen her stoned." It's mid-morning and this is her third joint. "I'll be fine until the afternoon," she murmurs. When she's having a "good" day, she'll smoke four or five joints. On a bad day, it'll be twice that. "I'm not a criminal!" she assures me. "This is not something I do recreationally!"

Since last November, Jane has had federal permission to have on her person 150 grams of marijuana and to store another 1,125 grams. She's also allowed to grow 25 plants outside or 10 plants inside.

Sadly, Jane's battle for relief is far from over. For one thing, there's no legal way for her to obtain the marijuana plants she needs. Like a scenario from Alice in Wonderland, Health Canada gives Jane and more than 800 other Canadians permission to use the drug, but doesn't actually supply it.

Federal experiments with confiscated marijuana plants have run into problems. Jane has managed to obtain some seeds and is growing them in buckets. The problem is, the plants won't be ready for harvesting until next year. Until then, she must buy from the street and that bothers her. "Every time I have to buy, I'm trapped," she exclaims. "I'm committing a crime, but I have no other source to get from." Buying from dealers means Jane can never be sure of the quality of what she's getting. "I've got some really good stuff and some really bad stuff, for which I paid $280 an ounce." Her pain is so unrelenting that she needs three to five grams of pot a day, which means her ounce is gone in a week or less. To date, Jane estimates she's spent about $10,000 on pot. "I'm putting it on my tax as medical expenses," she vows in all seriousness.

In the early days of her disease, Jane took a cocktail of prescribed drugs to ease the debilitating effects of her disease. The side effects were so severe, however, that she had to stop taking all but one. Hence the marijuana. "It eases my pain and gives me an appetite," she says. "It helps me sleep, helps my mood. I don't feel so sorry for myself any more." Jane continues to be awed by the effects of the marijuana. "Six years ago," she relates, "I was bed-bound, wheelchair-bound and I slept all the time. People had to come and bathe me." Today, she's better able to care for herself and her family and is even studying for a degree. She feels she has regained a quality of life she'd lost to the disease. Unfortunately, pot permits are valid for only one year, which means Jane must reapply. And therein lies a big problem. Originally, permits were granted based on a two-page letter from a family doctor. Today, there's a new application process, one involving a 32-page form and requiring the signature of a pain specialist. Jane is disheartened. "Who knows more about me than my family doctor," she fumes.

Frustrated but realistic, she's made an appointment at the pain clinic in Halifax. Worryingly, the earliest appointment she could get was in 19 months. "So, what will you do?" I ask. "I won't stop," she growls. Jane is lobbying Health Canada fiercely for an extension. The last thing she wants is to be sent to jail and denied access to the one substance that helps her. "Guaranteed, I'll come out in a wheelchair and need hospital," she growls. Personally, I doubt it'll come to that. After spending a morning with Jane, my bet is that Health Canada stands no chance against this tigress. At least, I hope not. Postcript: Jane has been granted a one-month extension to her permit with the likelihood of a further five months to follow.

For more information on the medical use of marijuana, check

www.medicalmarihuana.ca

Copyright © 2002 The Halifax Herald Limited